This summer’s A-level results revealed a widening attainment gap between the north and south, with ministers facing renewed calls to target support to stem “growing disparity”. Samantha Booth looks at what could be behind the regional gaps…

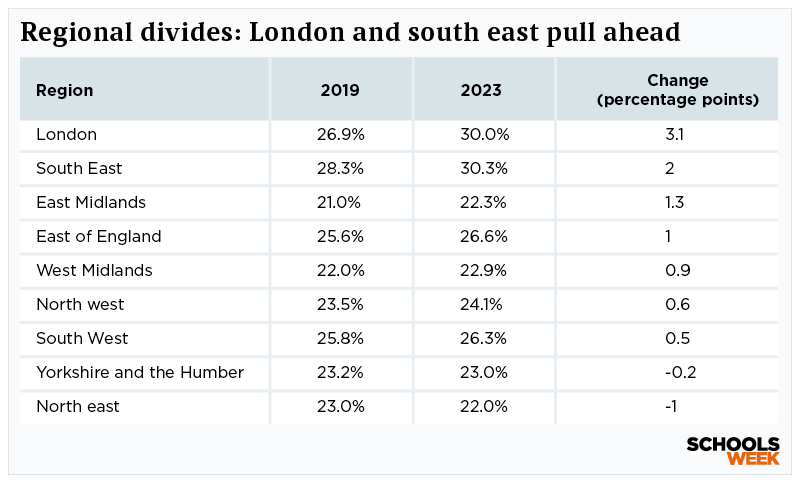

The north east now has the lowest proportion of A* and A grades – 22 per cent – which is lower than pre-pandemic. At the same time, London and the south east have recorded the biggest rises when compared to 2019.

It means the gap between the two top-performing regions and the rest of the country has widened.

Analysis by the Labour party found students across London and the south east were almost 40 per cent more likely to get top grades compared to the north east.

Stephen Morgan, the shadow schools minister, said the results showed the Conservatives had “failed to level the playing field” and were overseeing “the managed decline of educational standards”.

Are inflated pandemic grades having an impact?

Before we get into socio-economic factors, last week’s results have prompted concerns that some students who received inflated GCSE teacher grades might not have been properly prepared for their A-level courses.

Students sitting A-levels this year were awarded GCSEs based on teacher assessment in 2021.

Grades hit an all time high that year, but pupils in the north east saw the largest rise in results of grade 7 or above – a 49 per cent hike from 2019. This was followed by the south west with a 42.6 per cent rise.

In comparison, London had the smallest rise in top grades – a 34.2 per cent rise from pre-pandemic. This was 35.7 for the south east.

Analysis by FFT Education Datalab also shows more students are taking A-levels in England.

Between 2019 and this year, there was an 8 per cent rise in entries, which is above the 4 per cent rise in the number 18-year-olds.

So more pupils are taking the qualifications now than did pre-pandemic.

‘Inclusive sixth forms harder-hit’

Caroline Derbyshire, chair of the Headteachers’ Roundtable, said without grades confirmed by national exams, more inclusive sixth forms may have been hardest hit by this trend.

This is because they have taken on “students with grade 5 TAGs onto courses who may not have been secure in skills and subject knowledge”.

Michael Fordham, principal at Thetford Academy in Norfolk, said the issue may be exacerbated where sixth forms and post-16 establishments took on external students.

“With internal students you know them and may decide to accept them onto a course even if they narrowly missed entry requirements. But with external students you mostly rely on the grades, and those were harder to interpret in 2021.”

However, he believes the regional divide is “less to do with decisions made on admissions and more wider social structural issues”.

Dave Thomson, chief statistician at FFT Datalab, said it can be “difficult to make sense” of A-level attainment, as only about a third of 18-year-olds enter them.

North east hit harder by rising poverty

Disparities in poverty levels around the country also need to be taken into account.

Chris Zarraga, director of Schools North East, said “perennial issues” such as long-term deprivation have always existed in the north east but these were “massively compounded” by the pandemic.

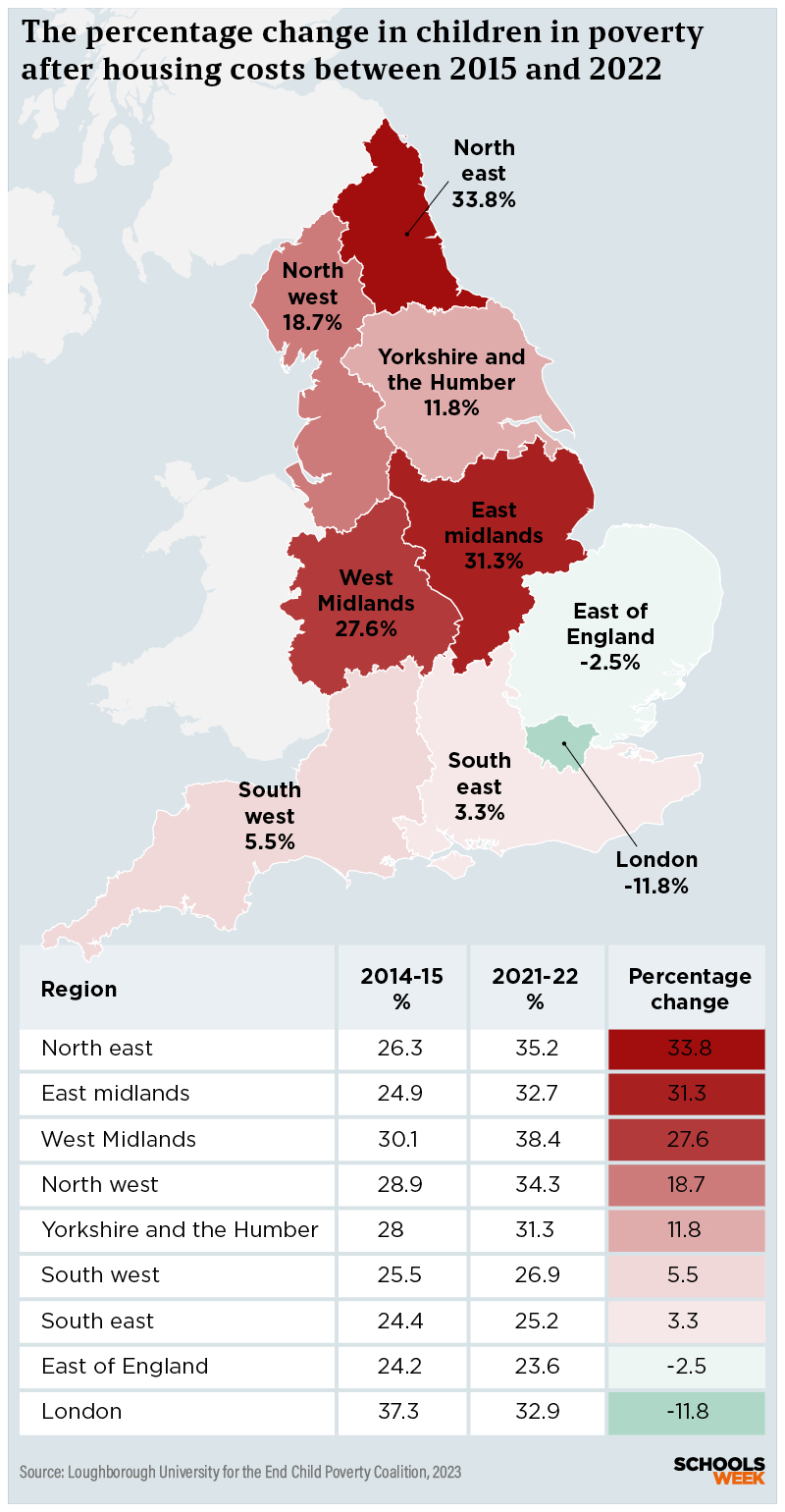

A study by Loughborough University for the End Child Poverty Coalition found an 8.8 per cent increase in children in poverty in England, after housing costs, between 2015 and 2022.

But in the north east this rose by 33.8 per cent, compared to an 11.8 per cent drop in London.

Middlesbrough, in the north east, had the largest increase by council area – a rise of 41.4 per cent.

Rates of food insecurity during the pandemic were also highest in the north east and north west (15 and 12 per cent), according to a Covid social mobility and opportunities study (COSMO).

These rates were lowest in the south east and the east of England (nine and seven per cent).

The study also found that families who used food banks during the pandemic received about half a grade per subject less in GCSE. But long-term disadvantage played a bigger role in this, researchers said.

‘Wealth and cultural divides’ drive disparities

Lee Elliot Major, social mobility professor at the University of Exeter, warned regional disparities are “primarily driven by wealth and cultural divides that shape children’s life prospects”.

The latest government data shows 30.4 per cent of children in north east state-schools were eligible for free school meals this year, compared to 18.8 per cent in the south east and 25.8 per cent in London.

However, the south east has seen a 90 per cent rise since 2015-16, compared to 65 per cent in the north east and 47 per cent in London.

Andy Byers, headteacher at Framwellgate School in Durham, said “there’s no doubt” that disadvantage plays a “huge role” in the results disparities.

“The impact of the pandemic is clearly being felt everywhere, but it’s disproportionate in areas like the north east.”

Nick Hurn, chief executive of the Sunderland-based Bishop Wilkinson Catholic Education Trust, said in “general terms what we see is more disadvantaged children in the north east, predominantly from white working class backgrounds”

These pupils “typically suffer as a consequence of limited pre-school support and education and less engaged parents in relation to their learning”.

Further breakdowns of results by pupil characteristic won’t be published until the autumn, so we won’t know until then if the disadvantage gap has continued to widen. But many expect it to.

Covid impact ‘deep in the system’

The pandemic’s impact was also felt acutely in the north – in areas such as attendance, device access and catch-up schemes.

The government doesn’t publish attendance data for year 13 pupils.

But according to analysis of attendance rates for year 11s by Datalab, London had the best attendance rates, while those in the north east had among the worst earlier this year. However, the south east also had relatively high absence as well.

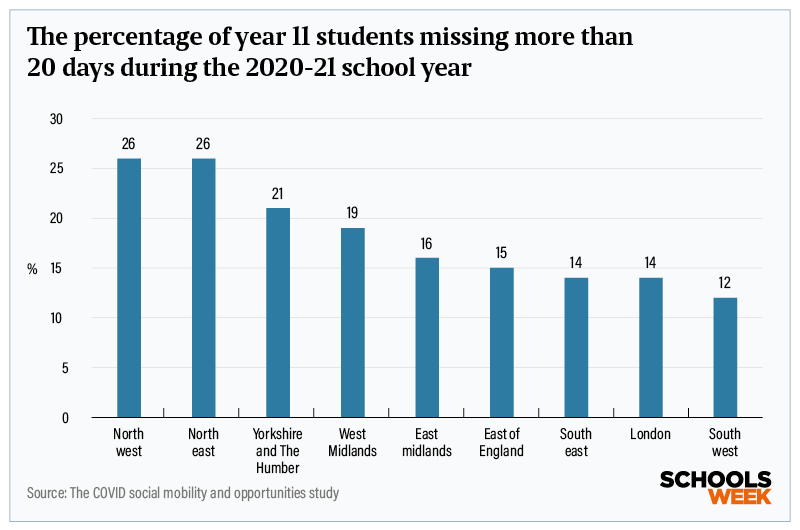

Over a quarter of this A-level cohort in the north east and north west missed more than 20 days of school during 2020-21 when they were in year 11, according to a COSMO study. This is compared to just 14 per cent in London and the south east.

COSMO also found that barriers to remote learning during lockdowns were more likely to be experienced by young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

Regionally, five per cent of pupils in the north east and west had no device during the first lockdown in 2020 compared to three per cent in London and the south east. But this gap narrowed slightly during the 2021 lockdown.

Live lessons were also more likely in London than in northern regions in both school lockdowns.

In the autumn term of 2021-22, the average reading learning loss in north east secondary schools was -3.1 months for the north east compared to -1.8 months in London.

But catch-up may have also been a problem earlier in the pandemic. Schools Week revealed how in 2020-21 the National Tutoring Programme was struggling to reach targets in the north.

Tim Oates, assessment director at Cambridge Assessment and a curriculum adviser, said the Covid impact “is deep in the system and will be progressing up through successive school years for a considerable time to come”.

What needs to change?

Dr Jo Saxton, Ofqual chief regulator, told Schools Week the widening gap is “uncomfortable” but is a “mirror” for policy makers.

The ASCL school leaders’ union has now called on ministers to “review what factors have led to the widening of the regional attainment gap”.

Geoff Barton, general secretary, said: “We are sure that if it does this exercise it will find that it is closely associated with relative levels of disadvantage compounded by the impact of the Covid pandemic on disadvantaged communities and the subsequent cost-of-living crisis.”

Elliot Major said a “much stronger” regional approach to education while Hurn said a comprehensive strategy is needed to engage parents in their child’s education as well as expansion of “character development opportunities”.

The Department for Education said education investment areas would help with divides but “we know there’s still more to be done to make sure children from all over the country have the same opportunities to succeed to the highest levels”.

Your thoughts