The government has delayed implementation of its expectation that all schools offer a 32.5-hour week by a year.

The government announced last year it expected all schools to meet the target by this September.

But in guidance issued in what is for many schools the last week of term, the Department for Education said the deadline had been pushed back to September 2024 “in recognition of the pressures facing schools”.

Schools minister Nick Gibb said the expectation was “part of our ambition to give every pupil the opportunity to succeed”.

“Whilst the majority of schools are already delivering this commitment, schools will now have until September 2024 to meet this expectation. We have today published guidance to support them to do this.”

‘A result of their own dithering’

Geoff Barton, general secretary of school leaders’ union ASCL, said ministers “have been forced to introduce this delay as a result of their own dithering, with this guidance publishing a full year later than planned”.

“This is yet another example of the lack of respect schools have, sadly, come to expect in the government’s dealings with them.”

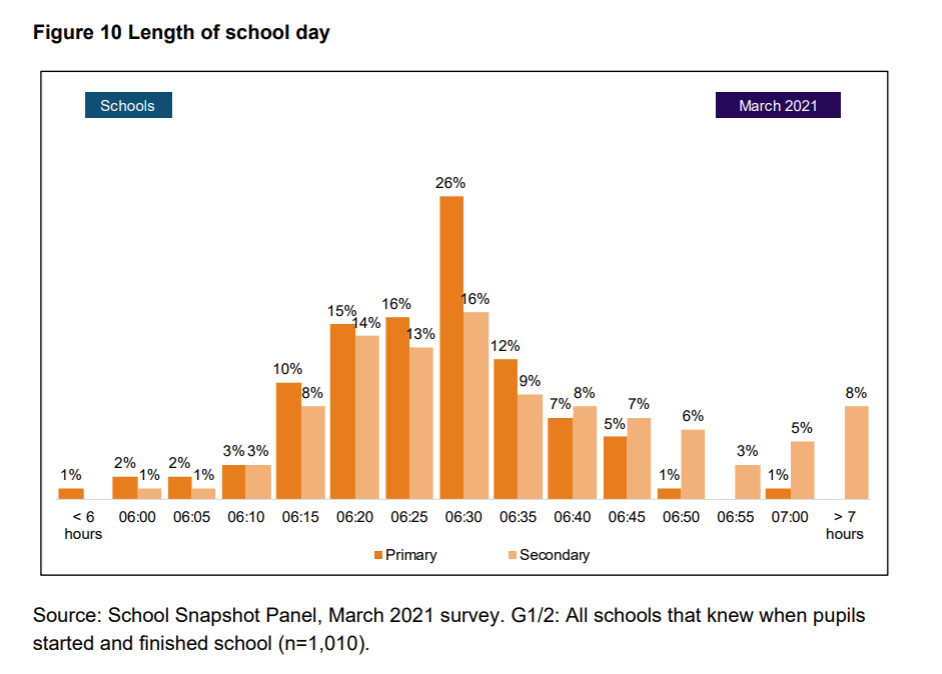

According to government survey data published in 2021, 52 per cent of primary schools and 62 per cent of secondary schools already run a day of six-and-a-half-hours or more.

A further 41 per cent of primary schools and 35 per cent of secondary schools run a day that is between six hours and fifteen minutes and six and a half hours long, meaning they would only need short extensions to comply.

Just 8 per cent of primary schools and 5 per cent of secondary schools run a school day of less than six hours and fifteen minutes.

James Bowen, assistant general secretary at school leaders’ union NAHT, said it was “unacceptable that the government left it so late to issue this guidance”.

“Schools had been left uncertain whether they needed to implement changes ahead of next term. The policy is a distraction and there is virtually no evidence to suggest adding a small amount of time to the school day will benefit pupils.”

The DfE’s guidance, which is non-statutory, said “some schools will already have increased their hours in response to the expectation set in the white paper”.

“Any mainstream state-funded school that does not yet meet the minimum expectation of 32.5 hours should be working towards doing so by September 2024 at the latest.”

Here’s what we learned from the guidance…

1. Prioritise extra lessons over breaks

Schools planning to increase their hours by half an hour or more should “first consider prioritising an increase to lesson time”.

Those only needing to add a short amount of time “may want to consider incorporating short activities which meet school priorities into their timetable, for example daily reading practice”.

Any increases to breaks “should be proportionate and bring value to the school week, for example by providing opportunities for sport and other enrichment activities”.

2. Make up the time if finishing early

All schools should deliver a “substantive high-quality morning and afternoon session in every school day”.

Those that want to finish earlier on specific days, for example for “religious observances”, should “offer longer hours on the remaining days so that they meet the minimum expectation over the course of the week”.

Secondary schools “may want to consider consolidating the additional time needed to meet a 32.5 hour week into a block of additional time on one or two days of the week”.

3. Expectation must be met within teacher hours cap

Teachers’ hours are technically capped at 1,265 hours per year, though in reality most teachers work more.

The DfE said any additional teacher time needed to deliver a longer school week “will need to be incorporated into a school’s directed time allocations”.

4. Ofsted will expect ‘clear rationale’

During Ofsted inspections, where it is “clear that increasing the overall time pupils spend in school to at least 32.5 hours per week would improve the quality of education, inspectors will reflect this in their evaluation of the school, and in the inspection report”.

If a school is not meeting the minimum expectation, and this impacts on the quality of education, inspectors will “expect schools to set out a clear rationale for this and understand what impact it has on the quality of education”.

They will also “want to understand what plans are in place to meet the minimum expectation”. But Ofsted is “mindful that some schools will be transitioning towards meeting the minimum expectation over the period to September 2024”.

5. Schools already meeting expectation urged to do more

And schools already meeting the expectation “may wish to consider increasing their school week further to provide additional opportunities for pupils, either as part of the core week or by providing activities that are optional for pupils”.

6. Consult councils on transport impact

Leaders should also consult “relevant local authorities” as early as possible in advance of changes to “minimise any unintended consequences or costs for school transport”.

The DfE acknowledged changes to transport arrangements “may require the local authority to re-negotiate existing contracts with transport operators, or tender for new ones”.

7. Staff contracts may need to change

Schools also need to “consult and inform staff with adequate notice”.

This includes “all staff who will be affected by any change, for example sport coaches, wraparound care providers and peripatetic music teachers”.

Again, the DfE said schools “may need to review and amend the contracts of some staff, especially those paid on an hourly basis”.

School staff always worked for 32.5 hrs per week when I was in Education. I didn’t realise shorter working hours was a “thing” until my son ( a teacher ) dropped it out one day. I was shocked, to tell the truth, 32.5 h s isn’t a long working day.

“schools already meeting the expectation “may wish to consider increasing their school week further”

Yes, why stop at 32.5? Why not have a rolling programme of annual increases until the optimum teaching week is attained? 35? 40? Surely logic tells us that the more time pupils spend in school, they more they achieve, so why bother sending them home at all??

Or, since the guidance is non-statutory, schools could just ignore it, recognising it for the nonsense that it is.